The following conversation between Professor Harry Naar of Rider University and Louis Finkelstein took place on the occasion of an earlier exhibition there. Professor Naar has graciously permitted its inclusions here. (for the original catalog)

H.N. This exhibition is from 1971 to 1999. Why did you choose this time period? What did you want the viewer to recognize or become aware of?

L.F. For me the exhibit is to help me see what kind of a painter I am, that is, what is possible for me to paint. I think the whole question of what painting is and can be is a very open one, and, more than anything else, that’s what I’d like the viewer to get. The time span is based on the fact that my painting took a more serious tack during the course of a year which I spent in Aix-en-Provence (1971-1972) when I was on a sabbatical leave from teaching. From there, the show simply extends to what I am doing most recently.

H.N. How do you begin a work? What stimulates or supplies the impetus for you to create a particular image?

L.F. I begin variously. Sometimes, I work directly from the sight seen, familiar or new. I tend to work better from a familiar sight, but seen, at least for me, in a new way. At other times, I do one or more studies directly and then work in the studio from them. Sometimes, I start from drawings I’ve done in the past, because I see something to do that I hadn’t seen before. Sometimes, I start from a reminiscence or resonance of some work of art I’ve seen and desired to emulate whether by jealousy or curiosity.

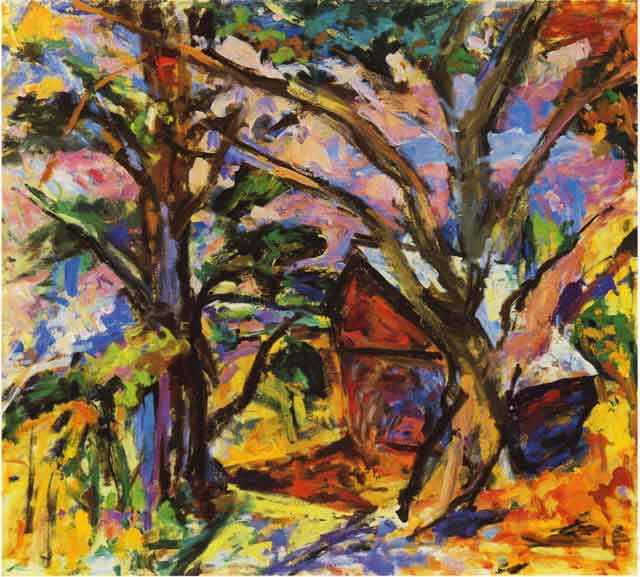

Hanover Center II 1998 oil on canvas 38 x 42 inches

H.N. For many artists, the act of drawing is the first step in discovering the shapes, the forms and the composition. What role does drawing play in the development of your paintings?

L.F. The first thing that comes to mind is that I do many more drawings than ever end up as paintings. I draw all the time, mainly as a way of exploring possibilities of form and subject. Some of the best are from masterworks of sculpture and painting, more for the enjoyment of their depth and precision of meaning than to use in painting.

When I hit on a drawing I want to make a painting from, I am very careful to preserve the proportions of the drawing as I start the painting. That is, I stretch up the canvas to conform with the proportions, sometimes cropping the drawing as a first editing, and then I enlarge the drawing systematically onto the canvas.

Drawing from observation on the motif, I use a fairly small pad so that I can see it all at once using pencil, and with pastel, I work at a larger size, up to 18 by 24. Sometimes, I paint directly from nature with no advance drawing, so that drawing is caught up in all the other decisions of the process. I hope that my having worked at drawing in other ways spills over in a spontaneous way.

H.N. It seems to me that most of your paintings are about the depiction of the representational world, but not in a literal, perceptual way because you combine the experience of the perceptual with the conceptual. When do you rely on these experiences in painting?

L.F. It’s hard for me to distinguish between what is perceptual and what is conceptual. What I seize upon in the visible world is always something particular that lures me to explore its possibilities as a painting form. Cezanne said, “To see is to conceive and to conceive is to compose.” I guess my motives go along that line. Sometimes, in the course of working, or even dreaming about my paintings, new forms, new themes emerge, and I follow them. I perceive them, but they are also conceptualized, that is, they become thematically important for themselves. Sometimes, the painting becomes more expressive of what moved me in the motif when I succeed in clarifying the form synthetically in the studio.

H.N. In your work, there seems to be a dialogue between the abstract, spontaneous application of paint and the representational, analytical approach. Would you explain this?

L.F. Again, it’s difficult for me to draw a distinction between them although, of course, there is a difference. Implicit in what I just said about the relation between the visual and the conceptual is that, primarily, I’m conscious of dealing with relations, relations which are essentially of pictorial forms on the canvas; although, naturally these refer to relations seen in nature. These relations are, for me what I call “thematic”, that is, like a musical theme, particular intelligibilization extracted from the flow of sensations. So there is no issue of simply objective representation. One of my teachers, Edwin Dickinson said, “representation is a bum aim, but you’ve got to deal with it.” Some of my paintings involve sheer automatism, putting down one element and then responding to its effect upon the whole for the next move. So that is where the spontaneity comes in. So far as the application of paint goes, I simply do what I can to make the forms work according to my view of what works. I can’t go any further than this to make them fit into some extrinsic idea of completeness. Sometimes, I elide certain aspects of description, usually in favor of going along with what the paint does. This is purely empirical, by trial and error. I can’t tell in advance what will work. Therefore, although there are many things in my work which are spontaneous, I never think of myself as a performer with paint. Of course, I envy a number of DeKoonings where he seems to do both at the same time; perform with the paint application, and arrive at a complete and logical structure. I suspect that, for him, the two are related. The same goes for Soutine. Compared to those two, I just plug along.

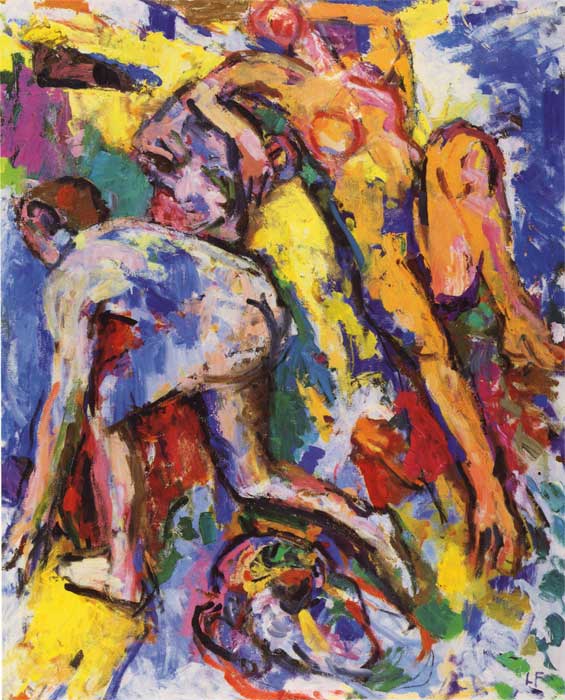

Falling 1997 oil on canvas 70 x 54 inches

H.N. What role does color play in your work?

L.F. Color plays a very big role. For me, there are several aspects to color. First, is that a given color has a different appearance depending on what color it is with, both adjacent to it and throughout the composition. So sheer visibility is a concern. Then there is the matter of color interval or distance which orders colors into groups and brings out color shapes in varying degrees of contrast and similarity. Then there is what I call the “color statement”, a phrase I learned from one of my early teachers. It refers to the overall expressive effect of colors in an ensemble. Some people call this “color harmony”; but I think the effect is not preset like the rules of harmony in music, but rather is discovered anew in each painting. It is associated with the decorative aspect of painting.

Beyond this, each successive increment of color changes the relations of volumes and space throughout a given painting. Sometimes, I will rework all the other elements of a painting–the drawing, the composition–in order to accommodate this factor. Lately, I have been shifting my priorities between this consideration, which I call the “plastic function” of colors, and the color statement, but only to a degree. The three dimensional coherence remains dominant. I reason about color through color theory, but ultimately, the decisions have to be arrived at by intuition.

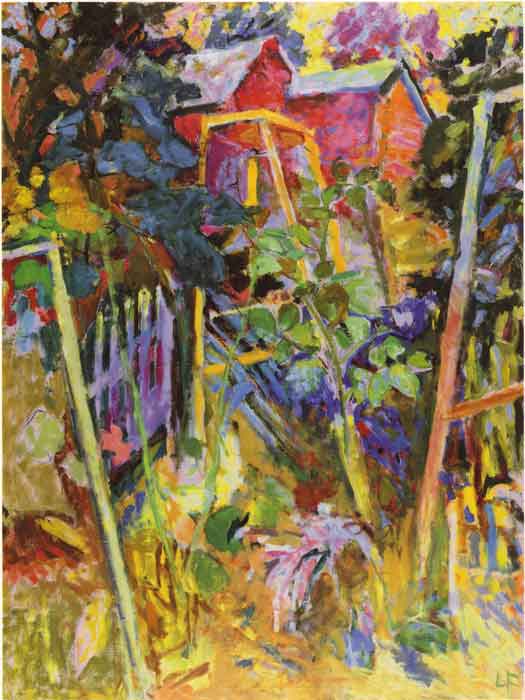

Nan’s Garden 1996 oil on canvas 59 x 44 inches

H.N. Two painters that I admire, Andre Derain and Jean Helion, were criticized throughout their lives for “changing styles”. Many critics have responded to your work in a similar way, by stating that you employ a variety of styles and themes, and that your ideas fluctuate. That you move freely in your paintings, creating themes and styles (representative to abstract to narrative figuration). What are your feelings about this? Please explain them.

L.F. There are some artists who every time they pass wind, they think it’s a work of art. I am the opposite. I am very doubting. I start any number of paintings I don’t know how to finish. Sometimes, they hang around for years. Sometimes, I paint over them or throw them out. My involvement in painting is in the exploration of painting language, not simply in making products. By the “language of painting”, I mean all the properties that are intrinsic to painting–shape, line, color, volume, space, and so on-and how they are understood. How sometimes shape is dominant, sometimes volume. How color has different roles in different contexts. How the treatment of local forms in a particular way poses requirements for the overall scheme and vice-versa.

The possible variations built into the nature of painting are, in a way, parallel to the way recombining words yields so many different meanings, even whole vistas of meaning. Through the recombining of elements and relations, paintings produce in us various emotions, affects, reminiscences which we would not have without them, and these are not used up any more than poetry is used up. When Clement Greenberg asserted the essence of painting flatness, I think he was off the mark by being both too literal and too narrow, and this gave formalism a bad name which it didn’t deserve. In my view, the essential nature of painting is that being flat, and also, very importantly, being bounded so that it consists of necessarily mutually defining relationships, it succeeds in embodying so many feelings and experiences, many of which we would never have but for the existence of the paintings which convey them.

The reported death, or marginality, of painting by what passes nowadays for a significant portion of the art

community, is the product of several factors: ignorance combined with opportunism; a decline in teaching and in thinking due, among other things, to the default of serious criticism; and particularly to the desire, on the part of people who have had no real experience of painting, to exercise control over it. My exploration of the language of painting, and my exposition of it in teaching and writing, is a small attempt to redress the balance.

Two Figures 1998 oil on canvas 54 x 44 inches

H.N. What artists have played an important role in

developing and forming your artistic vision, and why?

L.F. Well, first of all, Cezanne for the nobility of sentiment in his work, and for its sensuous richness. Early on, I was taken by John Marin for his animation and completeness–seeing the whole picture. Then, I was very influenced by my first wife, Gretna Campbell, who led me to paint directly from nature, although I eventually had to work my way away from her direct influence. Matisse, Monet, and Seurat for various aspects of color. Greco for the density of movement. Lately, I have been very much taken by Tiepolo for the way his forms turn in space. Overall, DeKooning has been a guiding star for his example of late modern seriousness and openness. Bonnard has also made a very important impression on me for various reasons: for the density and completeness of his paintings, for his willingness to work on them a long time, but above all, for one of his many aphorisms which is embedded in his work – “One speaks of obedience with regard to Nature; one might as well speak of obedience to the painting”. This sums up in another way what I was driving at in speaking about working synthetically in the studio.

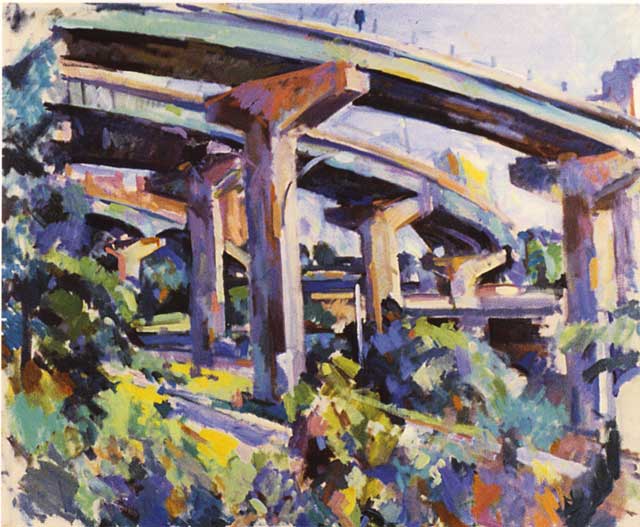

Kew Garden Interchange II 1978 oil on canvas 28 x 34 inches

H.N. In looking at all of your work and styles, there seems to be a landscape quality. What role has landscape played in helping form your vision?

L.F. When I went to art school, landscape was not taught in any systematic way, and it is still not taught in the way painting from figure and from still-life are. I think it should be. Maybe it’s only a matter of physical convenience. On the other hand; there were always around–in books, galleries, and museums–the example of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionists, who I think were heroic and revolutionary. Also, there was what was then called the American Scene.

I recall my sense of panic when I first went out with several of my fellow students to work directly from nature, and realized that nothing in my previous training had prepared me for it. Painters of my generation seemed to have slipped into it gradually since the landscape is always there, and seems to provide its own reason for painting it. For me, this was at first the parks of New York City, later streetscapes, and then, in the summertime, going away to the country–Maine, Connecticut, and New Jersey.

In one sense, painting landscape seems passive because you just go out and work from anything. Only later did I realize that landscape painting could have its own kind of structure and I was able to pick out certain guideposts, such as Claude Lorrain, Corot, and Constable who comes the Dutch. Nevertheless, except for the Dutch, landscape has had to struggle to he seen as serious art. There is a historical reason for this in that it doesn’t deal with the kind of ideas found in narrative and history painting. Another reason is that, at first blush, landscape doesn’t seem to have the order implicit in still-life and figure painting. This turns out, to me at least, to be an important virtue. Landscape can be near or far. It isn’t bounded, so you have

your own frame. Except for special cases, the space is not governed by linear perspective. The standards of description vary widely. So all of this has to be worked out by each individual.

Because one has to find one’s own particular order and technique, and even theme, landscape is very open in its possibilities. Because what a landscape looks like is not a given but only develops through the finding of formal consequences of the emergent relations on canvas, it is highly amenable to change and discovery. This is what I am continually conscious of, whether on motif or in the studio. The historian Walter Friedlander wrote a book, Portrait, Still-Life, Landscape, in which he compared the genres and concluded that landscape was intrinsically the most modern form, for reasons like these. Beyond that, there is in this country a tradition of regarding nature as a good in itself, and even a vehicle of moral lessons. While this is a little theological for me since I am focused on the formal expression, the feeling for nature as a value is in some way implicit. For me, the pictorial movement into deep space carries with it an emotional charge of all sorts of powerful feelings I can hardly articulate. Call it a sense of being in the world. It is there for me in a very immediate way.

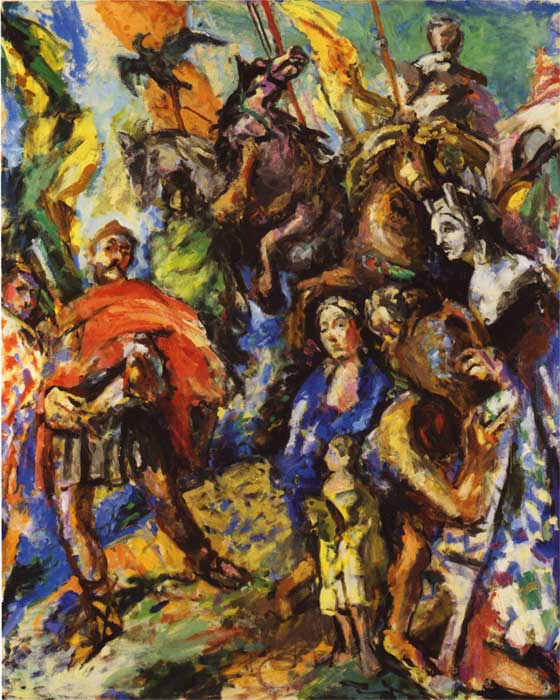

From Tiepolo’s Jugurtha 1998 oil on canvas 64 x 52 inches

H.N. You have taught and lectured at some of the best art departments in the· country, such as the Brooklyn Museum Art School, Philadelphia College of Art, Yale University Art School, New York Studio School, and Queens College. In 1979, the College Art Association awarded you the Distinguished Teaching of Art Award. How has teaching and writing about art affected your thinking and creativity in developing your painted images?

L.F. In the first place, it may well be that teaching and writing about art constitute my dominant form of thinking and creating, and the practice of painting the means to do that. The jury is still out on that. I think of them as co-equal and complementary. At certain times, my involvement in teaching, and in the administration which often went along with it, took time and focus away from my painting. In a larger view, however, I have learned a tremendous amount from teaching: having to prepare and present my ideas, seeing how they work out, going over many subject matters such as art history, design, color theory, as well as painting and drawing. I’ve even taught typography with profit, as well as several courses of my own invention. I’ve learned from what students produce, and also from my colleagues over the years, whose ideas and work differ from mine. I value the need for articulation of ideas which teaching demands. Reciprocally, I think painting is itself a kind of teaching, and in the modern situation, its own kind of liberal art, like literature or philosophy.

Forest of the Chateau Noir 1971 oil on canvas 32 x 36 inches